all new to me.

-30-

Almost inarguably, Thomas Piketty is among the most considered voices in the global discussion around socioeconomic inequality these days, and the contributions in his latest book, Capital and Ideology, are a clear enough justification for that fact. In his latest book, Picketty, an economic historian, catalogs and assesses the various mechanisms and beliefs justifying social and economic inequality–the inequality regimes—established and used in various societies–across the globe–from (give or take) the 14th Century to the present. He couples this assessment with objective analysis of the present and offers a fair bit of insight into how the understanding of this past may be useful today.

The scholarship is profound. Coming in at a little over 1,000 pages the book does not limit its focus to the history of inequality of Piketty’s native France, or even to Europe. Significant portions of this book cover the slavery economies of Haiti and other Caribbean Nations, The American South, Brazil, even Britain’s involvement in the trade of enslaved people. The treatment is not brief and in reviewing each instance for the unique characteristics of how inequality was established, discussed, and mainly justified, effort is taken to extract the lessons arising from each. While no work can be exhaustive on such topics, the care is apparent and the insight Piketty provides on these societies was illuminating to me in so many more ways than I can take the time to elaborate. The moral justifications of European Imperialism in Africa are discussed–not just along the Atlantic coast, but in North Africa and extending into the Middle East (Asia) as well–with a particularly insightful explanation of how the preceding military adventures between the countries of Europe simultaneously equipped these ‘colonial’ powers in their pursuits and prepared the economic impetus (if not moral justifications) for all that was to be done. From Africa, Piketty simply rounds the horn and spends time focusing on the role of the British in India and the profound and lasting effects this involvement created via caste and other mechanisms before proceeding to China and the Far East to discuss both the inequality regimes found there and those imposed by the European powers of the era.

And this is only the first 400 pages.

As the book progresses, history retains its overall dominance in Piketty’s narrative, while social science increasingly begins to contribute to the work. Grounded in the past, salient aspects from others’ scholarship are added to flesh out a fuller understanding of the dynamics at play in these various societies as the years pass. The book is not precisely chronological, however, it is astonishingly organized, particularly in light of its impressive breadth. “A mile wide but an inch deep” is a phrase often heard in areas where breadth is mentioned as a virtue, but that phrase does not belong here. The book is not a page-turner exactly, but it is not remotely a slog either. It is fascinating. There are over a thousand pages of text in the hardback, so — y’know…it takes time — but it is not dull and it does not belabor. The assertiveness of its statements comes from the work–scholarship that book shows–and not from the exuberant voice of an author clinging to moral sentiment to make his case.

But morals are not divorced from the text either. Moral impulse pervades the spaces in between as it were, and in a few instances moral questions are contrastingly put forth boldly for the reader’s consideration. There is no shortage of points for consideration, but two main assertions of the book are as follows:

First: Inequality Regimes are as old as dirt, and just about as varied. Every civilization we have ever created had some form of inequality, and that inequality was justified in some way by a dominant worldview (an ideology) that explained just why it was right and proper that certain folks had so much and others had so little (if anything). The justifications for inequalities, both within and between civilizations, are cloaked in various forms depending on the era and the society: divine providence, the mission-of-civilization, economic necessity, the inhumanity of the subjected, natural order, meritocracy, or some variation of nonsense relating to Horatio Alger and his goddamned bootstraps. In every society, those with more socioeconomic power–not necessarily those with the most, but often a plurality of factions that benefit from the inequality regime–align to maintain a belief that this inequality is justified. The poorest have always deserved it; the reasons just happened to change depending on the time and place. Without an ideological justification to explain inequality, the system would be in danger of collapse.

Second: There is no reason why any particular justification should be tolerated. Objectively, these inequality regimes are ideologies and Ideologies do not arise from some immutable truth revealed to those who just-so-happen to benefit the most from them. History has many switch points, often found in crises, per Piketty, and the individual trajectories of so many civilizations and the ideologies they employed (and employ today) are the product of the decisions made yesterday and the ones we all make going forward. As fervently as anyone may wish to argue to the contrary, positing that any particular truth objectively justifies societal inequality, independent of history, does not withstand scrutiny.

Of particular interest to me was Piketty’s discussion of political structures in the modern era – roughly since 1980. “…inequality has increased in nearly every region of the world since 1980, except in those countries that have always been highly inegalitarian,” he writes. He goes into a fair bit of detail in the recent political developments of France, Britain and the US, but he finds a common thread in each, coining (unless I missed the attribution) the terms “the Brahmin Left” and “the Merchant Right” to speak to broader trends transnationally. I confess that by the time I reached these ideas, I fully expected most of the book’s focus to be on The Right(TM) as the instigators and primary defenders of inequality. However, that is ludicrous in hindsight and–as stated “does not withstand scrutiny.” I only mention it here to affirm my own susceptibility to bias.

Piketty spares no page count though in laying out the failures of the Left and the complicity of those left-of-center–like myself–who having attained a certain degree of comfort owing to the benefits of (economically rewarded) education–reinforce the system, basically in collusion with the others benefiting from the system. Put simply: this is not a book about The 1%; this is not a book about left versus right. This is a book that does not shy away from the role the top several deciles of any socioeconomic order enjoy or at least reify to the detriment and peril of the remaining population, even accounting for the fact that these factions may not work hand-in-glove or even productively on many other matters. The work Piketty does on this point, much of if focussed on “the Brahmin Left” is commendable and personally, I feel a debt of gratitude for his focus on it.

There is so much research and so much said in this tome, but there is no reason for me to sum up Piketty’s conclusions – he does a fine job himself in the last few pages, a chapter surprisingly titled: Conclusion and there are plenty of reviews available elsewhere. I will say that as someone holding no academic background in history (outside of undergraduate general education requirements) or any background at all in economics–the journey is well worth the ride for all thousand pages. The expanse and scope of the scholarship illuminated much for me and connected numerous dots filling in more than a few gaps in my education — notably on ideas and topics not even mentioned in the book, just through its voluminous context. It is a fine book to pour through, bringing what you already know to the pages within. There is so much information inside, that I suspect it would inevitably provide contexts for a greater epistemic grounding for much that you already arrived with.

I cannot recommend the book enough.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital and Ideology. The Belknap Press of Harvard Press. 2019. pp. 1093. $39.95 (Hardcover). ISBN: 9780674980822

-30-

In John Dickerson’s latest book, The Hardest Job in the World, he mentions The Eisenhower Matrix, and presents it as a tool that President Dwight Eisenhower used. There are no shortages of concerns that people would love to bring to any President’s attention, but in his estimation, the President should only be focused on Quadrant 1 and Quadrant 2 issues–the important things–and must deal with the issues in the time frame appropriate to each.

I keep returning to the idea of this matrix. The simplicity disguises its effectiveness and it has become increasingly valuable to me since learning of it. Most of what I read is either non-fiction (predominantly in the social sciences) or news, and my media diet has never failed to provide concerns that I, as a citizen, am made aware of. In an election year–amid the volume swells & pounding of drums and when so many news events and issues are presented with such a feeling of importance–I feel this matrix really shines in identifying what is useful to focus on and avoid the traps of the season.

Quadrant 1 is the Important and Urgent: I would place things like public confidence in a free and fair election or getting the Covid-19 pandemic under control in this block. Quadrant 2 would be the Important and Non-Urgent: I would place something like Comprehensive Immigration Reform or Nuclear Non-Proliferation efforts in this block.

For Quadrants 3 and 4 “Less Important” feels like a more useful term. But for Quadrant 3, I would place restoring faith in Public Health Agencies and increasing public confidence in the value of expertise in specialized fields; in the distant corner of Quadrant 4, I might have some bit about the remodeling of the White House’s Rose Garden.

In any event, I just wanted to share this. I find it useful to have the language available to immediately recognize something as a Quadrant 3 or Quadrant 2 issue in my own day-to-day and perhaps someone else who had similarly never come across the Eisenhower Matrix may as well.

-30-

currently reading: Let Them Eat Tweets, Jacob S. Hacker & Paul Pierson

last full listen: Cities II by Thibault Cauvin

One of the biggest blind spots I had when living in North Florida, was a lack of interest in the estuaries and wetlands of N. Florida and S. Georgia. My favorite wild places as a young man in the area were the Okefenokee Swamp and the Long Leaf Pine forests of the Ocala and Osceola National Forests and I spent a fair amount of time tromping through them when I could. But nearby were hundreds of square miles along the Nassau River, the St. Marys, the Little and Big Satillas and all sorts of other tributaries and coastlands I largely neglected. Marshes, arguably more interesting–and unique in their abundance–were similarly neglected, outside of the areas on the edges I could walk to. The truly primitive areas are accessible only by boat.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot this year, having visited my folks before the pandemic hit the US–and driving down from Atlanta, looking at many of these places from the higway–staring into the distance with older eyes. In retrospect, it seems that to know the Region, not just certain forests, but the unique character of the region, one needs a canoe. These ecosystems simply dominate the geography and are among the last primitive / wild places in the area and to my mind, dominate the natural character of the place.

In any event – I just wanted to relay that point in case it lands with anyone. There is a lot of interesting outdoor ecology that you can’t just drive to in the area. As someone who strives to get well out into the wildernesses of the West Coast these days, it is interesting to consider that despite treks far afield to places like the Nantahala NF in NC, or the Everglades and Florida Bay far to the south, there were neglected areas in my own back yard, that could have been accessed more frequently with a modest investment in something as inexpensive as a used canoe or kayak.

-30-

Since the pandemic began, like many, I’ve been making a few sourdough loaves of bread each week and periodically posting the results online. After dialing in a basic formula and method, my main focus has been on experimenting with various types of flours to explore the flavor profiles of different types of wheat while striving for a particular aesthetic (dramatic rise, open and consistent crumb). Laura Dakin and I were passing comments online recently though and she indicated that she prefers a more sour loaf and tends to modify her approach (by season, even) to accommodate her taste. When she explained what she was doing to make a more sour loaf, I gave it some thought but quickly realized that I did not understand what microorganisms in the mix were doing.

If anyone isn’t familiar with it, sourdough is essentially an ecosystem. Folks who play with sourdough generally create and keep a small amount of starter on hand, which is simply a mix of flour and water serving as an environment for microorganisms — germs and fungus in this case (bacteria and yeast, respectively). Like any environment, it has a carrying capacity, and as the populations consume existing resources more are added to prevent the extinction of the organisms inside it. For reasons apparent to me now, I had mostly been considering the yeasts in the process of bread making and neglected the roles played by bacteria, despite the fact that the bacterial population may outnumber the yeast 100:1. Further, I did not ever really understand the biology of either organism and how they impacted flavor.

In the US however, the baking industry produces $423 Billion in economic activity each year, producing about $30 Billion in annual revenue. This incentivizes funding for scientific research on the topic from both government and industry. (there are scientific journals, even!) In the civic sphere, there are also Public Libraries. And most libraries have online databases allowing citizens to access much of this research from the comfort of their own home. Thus, what I’ve gathered so far:

The Bacteria:

There are generally two types of bacteria found in a healthy sourdough ecology: AAB and LAB (and I’ll get to that). Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis is a famous bacterium endemic to the Bay Area and is likely present in my starter since that is where I live. Its day-to-day in a sourdough environment consists of eating carbs (glucose, from the flour, after a bit) and producing–among other things–carbon dioxide (CO2), ethanol and lots of lactic acid as waste products. Hence, it is an LAB: Lactic-acid bacteria. This Lactic acid generates a taste profile akin to yogurt (for reasons) and is responsible for that mildly tangy profile in many sourdough breads. Any AAB in a starter’s environment do their bacterial business by consuming glucose *and ethanol*, and excreting large amounts of acetic acid (and CO2 as well as other compounds). Since acetic acid is the primary component in vinegar, this is the origin of faint notes one might describe as tart or vinegar-like in various sourdough breads. Generally, LAB is dominant in most cultures. AAB generally favors a more aerobic environment (bread dough is anaerobic for the most part), competes better at cooler temperatures and has a competitive disadvantage in the the presence of lactic acid. (LABs, in this case, have a certain advantage in being able “to shit where they eat” despite conventional wisdom advising to the contrary.) Additionally, certain organic acids produced by LABs have antifungal and antimicrobial properties that may hinder the ability of AABs to compete in a shared environment. The majority of microbial research on the topic has been on LAB historically although more interest is being paid to the role of AAB lately and more will be learned as a result.

Yeasts:

The yeasts are also hungry for glucose. But being fungi, they have evolved to generate enzymes useful in decomposing their environment into more useful constituent parts. In this context, the yeasts break down the starches from the flour, converting them to sugars. And in doing so, we now have the beginnings of a synergistic relationship. By way of analogy, the yeast process the wheat (flour) to create sugar (glucose). They are exceedingly efficient and generate a surplus that the bacteria can use for their own purposes. The yeast (along with the bacteria) consume the newly liberated glucose molecules and the yeast excretes CO2 and ethanol in the proess. The latter, if you recall, is then also able to be consumed by AAB. A certain long-term symbiosis can be achieved if the bacteria and the yeast are able to gain a foothold in the starter as they will create an environment where food will be available thanks to the yeast, and interlopers will be kept at bay by the aforementioned antimicrobial properties arising from the organic acids produced by the LAB species.

It’s kind of a beautiful thing. Particularly in the early days. A problem can arise from the ethanol production of the yeast after a spell though. Similar to how AAB does not do as well in the presence of the LAB’s primary waste product (lactic acid), LAB does not do so well in the presence of the yeast’s waste product (ethanol). So the balance can be precarious, but it is a fascinating ecology to consider. Three organisms at play: the yeast helping itself and providing one basic resource (glucose) to each type of bacterium, and a second resource (ethanol) to the ‘disadvantaged’ one’ in the process; the ‘disadvantaged’ bacterium removing a substance toxic to the dominant bacterium; the dominant bacterium generating a modicum of food (ethanol) in return and contributing mightily to the defense of the environment from outside organisms. All produce CO2, which is the mechanism behind the rising of the bread (without gas being generated, you’d just bake a brick). All have distinct niches and favorable conditions and the interplay is Sourdough ecology.

None of this tells you how to actually make a loaf of bread of course, but it is useful in considering how to adjust one’s process to foster and ecology that produces the bread you want. Particularly if one can control distinct conditions in the bread making process. Information on the variable of temperature–perhaps the easiest variable to measure and control for any mix–are below.

credit: JMonkey at http://www.thefreshloaf.com/

If the above is true–and why would you NOT believe something from someone named JMonkey you found on the internet?–at ranges outside of 65′ and 74’F, LAB populations can out-compete yeast.

JMonkey jokes aside, the graph holds up, supported by a paper published by the Journal of Applied and Environmental Microbiology: Modeling of Growth of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Candida milleri in Response to Process Parameters of Sourdough Fermentation. (authors: Michael G. Gänzle, Michaela Ehmann and Walter P. Hammes):

In the weeks to come, I’ll likely try to put this to practical use.

-30-

Veepstakes 2020: The choice is imminent they say. I am hoping for Elizabeth Warren, but politically, the selection seems kind of marginal for Biden. No matter who he selects, half the critics will say she is disqualifying, the other half will rail that the person they wanted him to pick was clearly a better choice. This will all be very loud and will feel very important. But in the end, electorally at least, it is not. Presidential Elections come and go, but one truth seems to always remain: No one votes for Vice President.

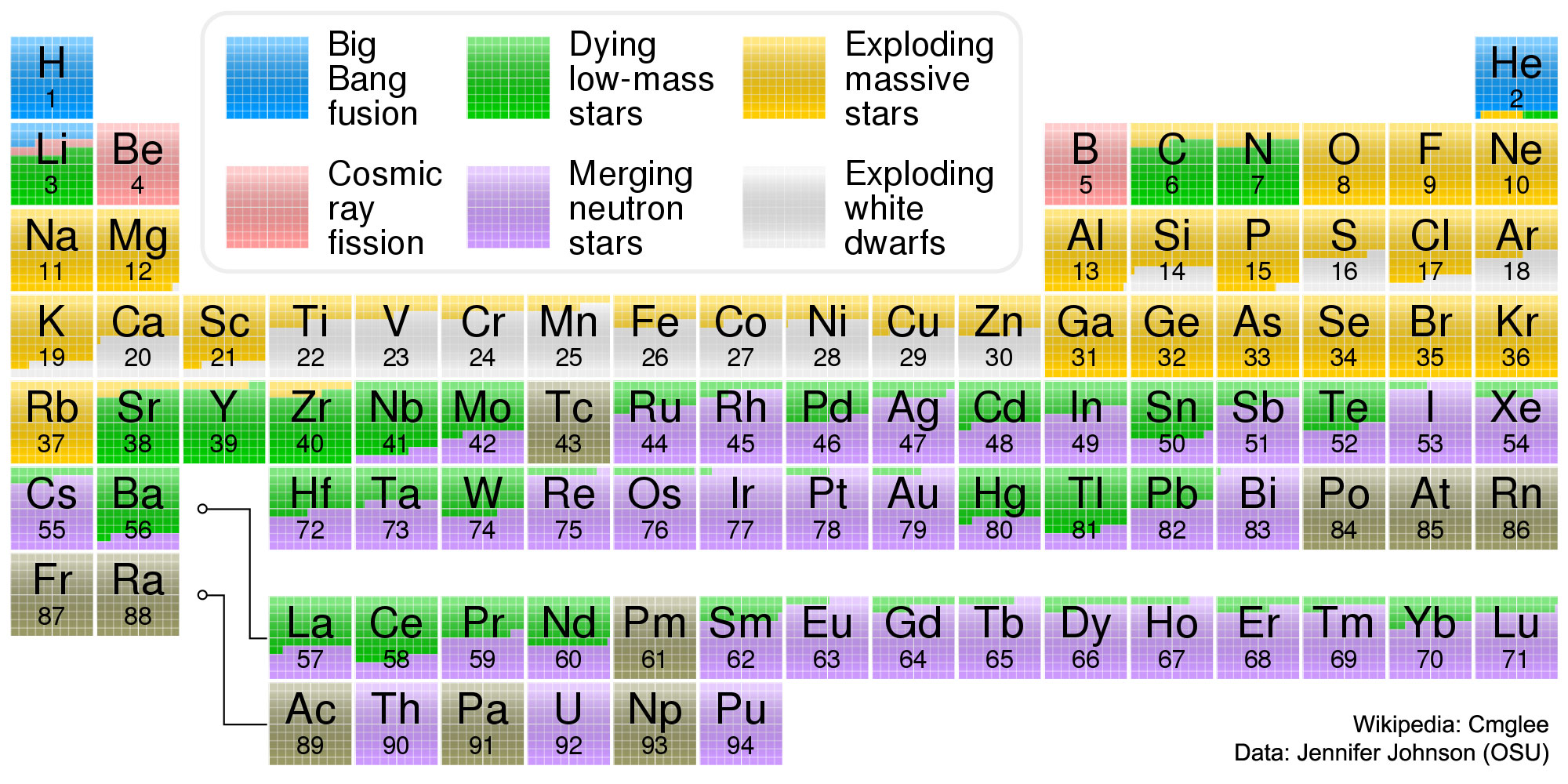

A few years ago a book I was reading piqued my interest in the origins of the elements (nucleosynthesis). I was floored by the idea that the ‘Big Bang’ produced Hydrogen and Helium (and some Lithium I guess) but that the rest of the elements–all those forms of matter represented on the periodic table, Oxygen, Gold, Uranium, etc.–were built later from those basic elements (mostly Hydrogen and Helium). The deep time and mind-boggling forces behind each element that we see under foot or in our environment fascinated me immensely. I bought a periodic chart, assembled it, hung it on my office wall so I could continue referencing atomic numbers easily as I read various titles on stellar evolution or astronomy as they discussed elemental outcomes arising from the interplay between gravity and stellar fusion. I wanted to remember the process that created each element, but perhaps not enough to do the maintenance to keep it all in working memory.

Enter Jennifer Johnson. A professor at Ohio State University who has created the Periodic Table of the Elements I always wanted — a nucleosythetic version providing the origins of each element!

This chart is simple enough to glance at, but really does quite a bit of work and is the first easy compendium I’ve ever encountered on nucleosynthesis. She really has done an amazing thing with this, imho.

“To abolish child labour you first have to make it visible”

GMB Akash is a photographer and photojournalist who does seriously good work.  The image above is from a series he did exploring child labor practices in Bangladesh. He tends to captures the dignity of people who find themselves in fairly dire plights amid a system of inequality that spans the globe as he turns up in Greece, Indonesia, Myanmar and elsewhere.

The image above is from a series he did exploring child labor practices in Bangladesh. He tends to captures the dignity of people who find themselves in fairly dire plights amid a system of inequality that spans the globe as he turns up in Greece, Indonesia, Myanmar and elsewhere.

If you had some time to quietly sit with a photo essay or two, I recommend his work.

Ed Yong has been doing the lord’s work in The Atlantic as of late. How the Pandemic Defeated America is a standout piece of writing that offers a clear eyed assessment of how the US has failed as a nation. He compiles mistakes and missed opportunities, squandered advantages, failures of policy, and ultimately, a failure of leadership. He also writes among the most damning appraisals of Presidential leadership I have ever seen:

No one should be shocked that a liar who has made almost 20,000 false or misleading claims during his presidency would lie about whether the U.S. had the pandemic under control; that a racist who gave birth to birtherism would do little to stop a virus that was disproportionately killing Black people; that a xenophobe who presided over the creation of new immigrant-detention centers would order meatpacking plants with a substantial immigrant workforce to remain open; that a cruel man devoid of empathy would fail to calm fearful citizens; that a narcissist who cannot stand to be upstaged would refuse to tap the deep well of experts at his disposal; that a scion of nepotism would hand control of a shadow coronavirus task force to his unqualified son-in-law; that an armchair polymath would claim to have a “natural ability” at medicine and display it by wondering out loud about the curative potential of injecting disinfectant; that an egotist incapable of admitting failure would try to distract from his greatest one by blaming China, defunding the WHO, and promoting miracle drugs; or that a president who has been shielded by his party from any shred of accountability would say, when asked about the lack of testing, “I don’t take any responsibility at all.”

He follows with:

Trump is a comorbidity of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

In other news:

A good idea in life is to simply start with the facts. And as it so happens in this criminal complaint against licensed securities broker and financial representative Michael Carter, the facts begin on Page 4.

Financial advisor broke the law with some clients. Stole some money, probably going to jail. Sounds boring, right? Srsly… check it out. It is astonishing.

Again… the facts start on page 4.

What a tangled web…

Finally, about twenty five years ago I heard a live version of a jazz/ragtime/big band ensemble belting out Some of These Days and fell in love with the song. The source must have been the radio, because it sent me down a rabbit hole searching for THAT version again – a quest I’m not sure I ever successfully completed. It was perhaps the first song I ever made a sustained and considered effort to hear from as many sources as possible (although it is possible that ‘Round Midnight might have come first for me). Recently, after not hearing this song in many years–perhaps a decade or more–a version crossed my path that was so well done and unique that I feel compelled to share. It is just so good, so pure. Please enjoy:

currently reading: Capital and Ideology, Thomas Piketty

last full listen: Obscured by Clouds, Pink Floyd

-30-

“[like] a hospital that invests mightily in palliative care while elimating the oncology department.” –The Economist, describing the US approach to economic stimulus in this pandemic

Following Congressional approval, on March 6th, 2020 $8.3 Billion in emergency funding was authorized for federal agencies to respond to the pandemic.

Twelve days later, $192 Billion in ‘Phase II relief’ was authorized for paid sick leave, tax credits, and free COVID-19 testing, and more.

Seven days later, March 25th: $2.2 Trillion was authorized through the CARES Act.

Congress is now discussing the next round of stimulus and the public discussion will be focused on the terms of that debate going forward, but I did want to formulate some thoughts on the topic.

All of April, May and June have passed since the CARES Act was signed into law. There is a week left in July, and we still have no national plan, just “guidance to the governors” from a hodge-podge of agencies coordinated enough to produce material on the subject of the Coronavirus. Some 13% of GDP has been spent (so far this year) on economic stimulus alone. While many disagree on what the funding above should have looked like, there is consensus that funding was necessary in March to prevent the further contraction or collapse of US economic activity. No serious person believes there won’t be additional stimulus to come.

Back in early March polling data pointed to increasing polarization around issues related to COVID-19. It seemed clear the body politic was not going to take a conservative appproach to the new virus that had emerged but wanted to maintain the status quo as much as possible. I honestly did not expect the polarization to have as much staying power as it did though–even after some folks started to valorize the idea of at least expressing a willingness to die for the economy later in the month. I estimated that once the cases reached a certain prevalance–frankly, once enough people, in enough places, had either died or had their health irreversably impaired–the risk of death and permanent loss of health would be taken seriously, and the competing narratives would align. Doing what it took to minimize cases would be seen as the best approach to sustainably reinvigorate economic activity after all the “if you build open it, they will come” attempts failed.

By April 15th, 25,668 deaths in the US had been attributed to COVID-19; the polarization did not abate, it intensified. By May 15th, when over 84,000 Americans had died, the largest predictor of an individual’s views on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was party identification.

Today, almost 150,000 Americans have died from COVID-19. Economic activity is still hindered, not just here, but abroad; the E.U. just authorized a €1.8 Trillion plan to address the impacts of the pandemic four days ago. But as I think back, I largely expected that $2.2 Trillion we spent at the end of March, to do most of the heavy lifting. I suspected some additional funding might be in order to tidy things up after America had bent the curve, overcome logistical issues or met its manufacturing challenges. But I largely expected America to do better than it did.

H.R. 6800, The HEROES Act currently proposed by the House is reported to provide $3 Trillion in COVID-19 response. It is almost impossible to argue that people don’t need help. But it occurs to me–in a way that it did not the last time we were here–that unless there is leadership of the sort that can unify the country in an effective course of action stopping the spread, this is just another stop gap measure. In other words, more of the same in terms of public health policy, will yield more of the same in terms of mortality and economic decline. The lesson since March is that there is no inevitable moment of truth where the body politic faces reality.

In the absence of leadership, this money buys us nothing – it only rents economic activity at a negotiated level until the next round rents more. All while people continue facing reduced employment options, many of which increase the risks to the health of themselves and their families and more people continue to die.

-30-

“Aren’t you worried? Going alone?”

I don’t get into the wilderness nearly as much as I would prefer, but from time to time I do. And in the days leading up to these excursions, I usually just can’t shut up about it either. Other folks (usually co-workers) inquire on the danger or risk levels involved with being alone and distant in the Mountains and the question that is asked most often is “aren’t you scared?” I usually explain that this isn’t my first trip, that I have a fair amount of experience, or rattle off equipment that reduces the liklihood of truly dire outcomes, and basically just minimize any risks associated with being in remote nature, alone, unsupported.

The truth of the matter though is that fear is a part of the experience, and yes — of course I worry; of course I have some fear.

On my latest trip, a planned 6-day trip surveying the Emigrant, Yosemite and Hoover wildernesses of California’s Sierra Mountains I spent a lot of time in the lead-up thinking negative thoughts about the entire thing. First, I was worried about the mosquitoes – and particularly worried about my committment to the mileage in the face of undeterred swarms. How would I react if they simply did not let up and my repellent wasn’t doing the trick at the height of mosquito season? I was worried about the possibility of spraining an ankle or breaking a bone, alone, 25 trail-miles and 2 days away from a car. I was worried about car problems getting there or back, critical gear failures deep into the wilderness, Mountain Lion encounters that might completely re-route my path in country with not a lot of options. Probably most significantly, I worried about wasting six days of possibility–days which I could devote to anything–but invested in a project that I might actually discover wasn’t so important to me after all. I was afraid I’d get a few miles or a day and a half into it, by myself, and think “meh – I’ve done this before, elsewhere, but I think I’d rather just go home.”

The solitude of backpacking solo makes it a radically different experience than ‘normal backpacking’ (with others) in my estimation, particularly the deeper one goes into remote spaces. Years ago, on a planned 4 day trip, I drove five and a half hours at night to get to a particular trailhead by morning, then hiked all day to get to a certain spot. I set up camp in late afternoon, only to realize by nightfall that, having been in that drainage before, there was no sense of exploration or excitement motivating me to stay. I was in a spot, again, only this time, I had no one to talk to or share the experience with. I hiked out the next morning. When you are alone, there is no consensus to acheive; you can quit any time, just turn around.

For all my negative thoughts on this most recent trip however — negativity which increased in both frequency and intensity, the closer I got to the trailhead in time and distance — by the time I was fifteen minutes into the woods, it was all gone. The roughest period of doubt, in fact, was during the handful of miles from the Highway 108 turnoff to the trailhead itself. I was honestly considering just turning around and driving three hours back. And then, once on the trail, suddenly, they just melted away. I remember contemplating that evaporation for about a mile at least and then returning to it periodically over the days that followed. Whether there is a lesson there for other parts of one’s experiene I won’t bother arguing here, but I simply wanted to follow up on a decision I made while out there, that I would come back and at least be open about that fear and how it impacts me and argue for it being normal, reasonable and common.

-30-

Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway co-authored a book, published in 2010 under the title The Merchants of Doubt. The book outlines the use of disinformation–in the guise of honest skepticism–and details instances of bad-faith argumentation and action from industries facing regulation. In 2014, a filmmaker named Robert Kenner, inspired by the book, released a film of the same name. Ms. Oreskes continues to do research in this arena and published a book at the end of 2019 (which I can’t read) titled, Why Trust Science.

Her claim, “scientific knowledge is the intellectual and social consensus of affiliated experts based on the weight of available empircal evidence evaluated according to diverse but time-tested methodologies” speaks not to science as a method, but as consensus, arrived at through evidence. I like this.

In any event, the lecture she gives below is about fifty minutes in length, informative, and entertaining. Other videos are available online, including a recent discussion on how the anti-vaccination, climate-denial, and other movements seem to have prepared us for such a dismal pandemic response.

How to Talk to Coronavirus Skeptics is also a video that might be of use in some circles, perhaps. Ultimately, she has a lot to say about the discourse around and among those acting either in bad faith or with a surplus of motivated reasoning. Of particular revelation to me tonight was the idea of ‘implicatory denial‘ – an ideological distortion arising from the clash between evidence so contrary to one’s ideology, that accepatance of the evidence would render a deeply held principle (or principles) untenable. For those unable to part with the ideology, denial of the evidence is the only option to avoid its necessary implications. Her lectures are littered with gems and insights along this line, and if these are topics anyone is interested in, I would recommend searching her name and spending time with the results.

-30-