Every morning Orville Anders rises and digs amid the ruins of Los Verticalés. Once a marvel of architectural engineering, Los Verticalés now lies collapsed amid an apparently vast and unidentified desert. Developed by a visionary entrepreneur, Los Verticalés was designed to be a self-contained civilization of sorts, a modular skyscraper that could be expanded—upward and outward—as demand (and population) increased. At some point, it reached over 500 stories in height – but then shortly thereafter, the skyscraper collapsed in a single tragic event. Orville, and the others who camp around the wreckage, spend their days searching for reclaimable materials and for survivors, including Orville’s brother, Bernard, the lone known survivor of the collapse, buried somewhere deep within The Heap.

Bernard is buried in the rubble, trapped in the radio studio he was broadcasting from during the collapse. He spends his days broadcasting over the radio frequencies, taking calls from the surface and keeping hope alive for other survivors who may yet be found as a result of The Dig. Bernard has daily contact with his brother Orville in the evenings, the latter calling in to the radio station after the digging of the day is completed. The calls are broadcast live and eventually, as it happens, they come to be among the most sought after moments of media across the world; folks far and wide tune in to hear the brothers talk. One brother buried alive, with no idea where he is or how to explain how to reach him, and the other with just a shovel and hope – also with no idea how to reach him.

It isn’t long until the powers that be have just one small question for Orville: during his daily conversations with his buried brother, would he mind just quickly saying a quick word from our sponsors?

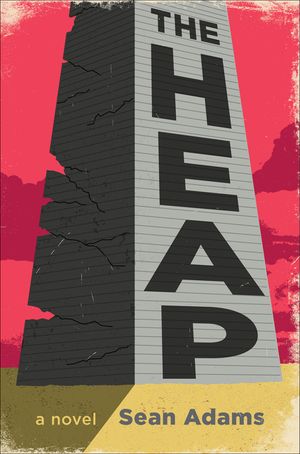

And with the ask, the book is off and running. Doing a not inconsiderable amount of work with the metaphor described above, the author, Sean Adams, takes a mighty swing at parodying our current moment. Writing in a braided narrative style for roughly 300 pages, Adams takes turns expressing narrative flourishes of absurdity, unfairness and other ideas that make you tilt your head ever so and wince a little, wondering just how much of what you just read actually applies to the actual world you actually inhabit. In this trick, ongoing as it is, The Heap ends up as an impressively competent reference point; the reader can crawl around in the narrative gauging where we are — actually, corporeally— in the current Zeitgeist.

Where I’m from, that last part is fancy talk, and I should pause here to make sure it is understood that the voice expressed in the book is not at all fancy. In fact, that is probably the heftiest critique I have for the The Heap, namely that the writing is kept to about a tenth grade reading level. It reminded me a great deal (for reasons) of George Orwell’s 1984. The procession of narrative – sequential and staccato sentences in a just-the-facts-ma’am style moved the book along quickly, but definitely at the cost of depth. The plot is superficial—consistently so, to its credit; the characters are all about an inch deep, but it still works. The book tells a tale; it is not playing with language. Your favorite sentence will not be found in this book. The tale is dystopic and expressed in a uniform voice. The book isn’t great – not in the way that the greatest novels are great at least – but The Heap is great fun, and Sean Adams deserves any success that comes his way for having written it.

Leave a comment